The fuels that power our cars and trucks contain carbon that turns into carbon dioxide when burned in an engine.

The buildup of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere has led to a rapidly changing global climate.

Transportation produces more greenhouses gases (also known as carbon emissions) than any other economic sector in the United States.

If we reduce the emissions from transportation, we will not only reduce our impact on the climate but also improve air quality in our cities and communities and reduce oil use and dependence

A Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) is a policy and a performance standard that requires transportation fuel producers and suppliers to lower the carbon intensity (CI) of their fuels.

The Carbon Intensity (CI) of a fuel is the total amount of carbon emitted per unit of fuel energy. It is calculated using Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA).

The baseline fuels under the standard are gasoline and diesel. Lower carbon alternatives to gasoline and diesel are not limited to liquid fuels, and include biofuels, electricity, hydrogen, and even natural gas.

A LCFS policy combines regulatory and market-based mechanisms by design, which is more durable and acceptable than policies that only use one or the other.

It is different from other policies because it is technology and fuel neutral and does not choose winning fuels on the market through direct regulation or subsidies.

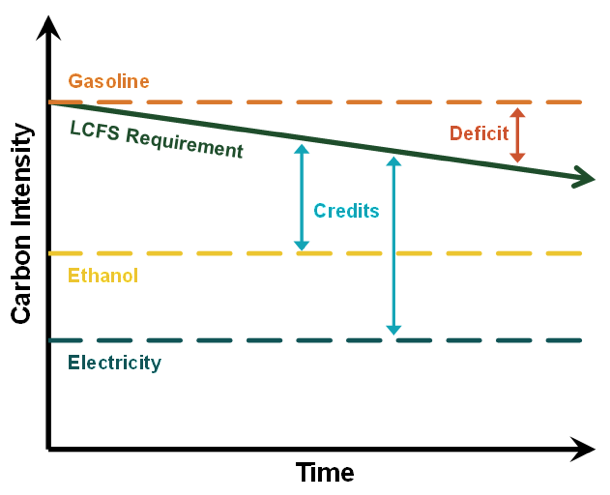

A LCFS establishes a requirement for the reduction in the average transportation fuel carbon intensity (CI) over a period of time.

For example, California’s LCFS adopted in 2009 required the average CI to be reduced by 10% between 2010 and 2020. The annual target typically decreases each year over the defined period.

Like cap-and-trade programs, credits and deficits are generated that may be bought and sold on a market by fuel producers and suppliers.

Fuels above the standard generate deficits, and fuels below the standard generate credits.

Fuel producers and suppliers can meet the requirements by:

As shown in the figure to the left, the average carbon intensity (CI) requirement under a LCFS decreases over time. Higher carbon fuels, such as gasoline, will generate deficits because its CI is typically over the requirement.

Lower carbon fuels, such as ethanol and electricity, will generate credits because their CIs are typically under the requirement (note that actual CI values will vary depending on factors like fuel source, processing technology, and other considerations).

To comply with an LCFS, high carbon fuel producers and suppliers must offset their higher CI fuels by producing or purchasing low-carbon fuels or credits, which will lower the overall average CI of their fuels.

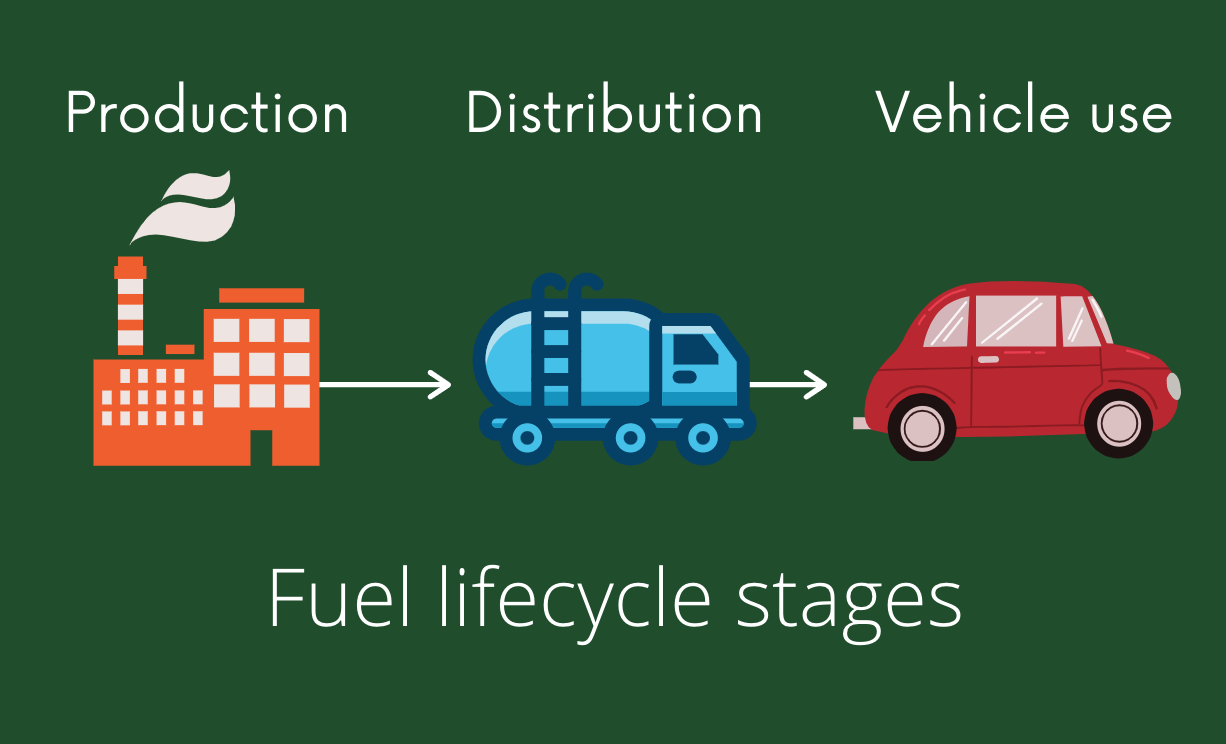

LCA is an analysis tool for assessing environmental impacts associated with the life-cycle of a product, process, or service.

For transportation fuels, a life-cycle assessment typically considers direct emissions from all stages in the life of a fuel: how it is produced, distributed, and ultimately used.

This is commonly referred to as “well-to-wheels” analysis. A well-established and publicly available tool for transportation fuel LCA is the Greenhouse Gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy Use in Transportation (GREET) model developed and maintained by Argonne National Laboratory.

A LCFS policy may also include indirect emissions for a fuel, such as those from indirect land-use change (ILUC) that may result from increased biofuel production.

Under a LCFS, fuels compete based on their life-cycle emissions, reported as their CI. Improvements in technology have the potential to reduce the life-cycle emissions of all fuels, including gasoline and diesel.

California was the first to adopt an LCFS in 2009, followed by similar policies in Oregon, British Columbia, and the European Union (EU).

In the last decade, these programs have proven to be an effective way to decarbonize fuels and reduce transportation emissions.

An increasing number of states and regions are considering adopting a LCFS or similar policy to reduce their transportation emissions, and there has even been a push for a national policy.

In Colorado, transportation emissions are currently the second-largest source of greenhouse gas emissions, behind electricity generation, and one of the largest contributors to ozone pollution.

In order to protect and preserve Colorado’s unique natural environments and Coloradan’s health and way of life, transportation emissions must be reduced.

A LCFS has the potential to provide air quality, health, and economic benefits across the state.

But Colorado cannot simply adopt another state’s LCFS, such as California’s, as each state and region has different characteristics that must be considered.